Who better, perhaps, to write a detective story than a semiotician like Umberto Eco – a theorist and practitioner of the abstruse academic art that studies signs and meanings? Linguists and semioticians remind us that reading itself – from the primary act of deciphering letters and words to the final act of interpreting what we've read – is like solving a mystery by piecing together signs and clues. It would certainly be impossible to accuse Eco of having written a dry academic novel.īut mysteries also draw their appeal from another source, the basic reason we read at all: the desire to find out, to discover explanations for the unexplained, to search out meaning. And the corpses of monks keep turning up when least expected.

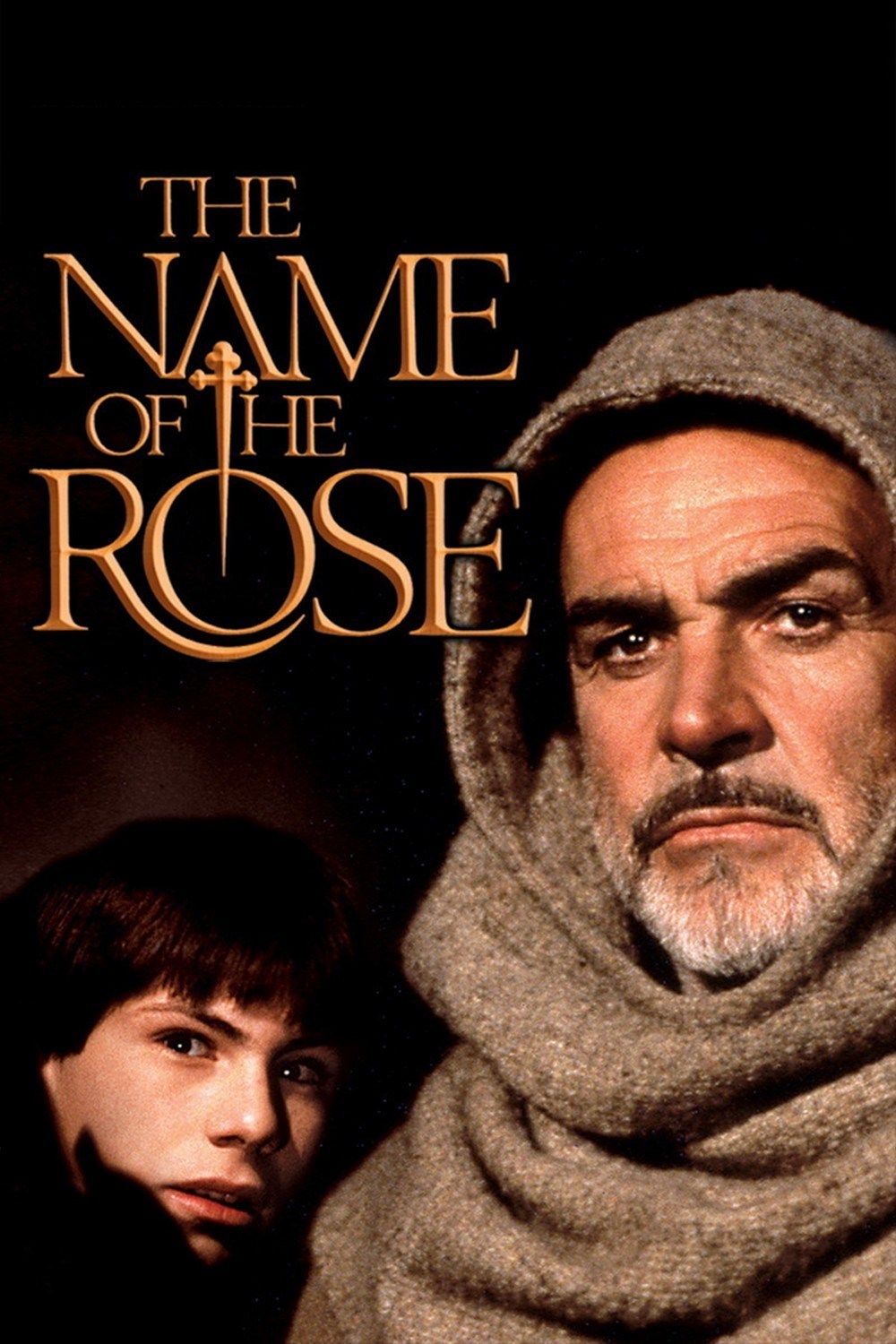

Innocent people are being burned as witches and heretics. What the great medieval historian Huizinga called the mingled odor of blood and roses is in the air, with the emphasis on the blood. The story unfolds in an atmosphere thick with hostility and intrigue. ''The Name of the Rose'' is no exception. Mysteries, to be sure, are always popular, in large part because they deal with the emotionally charged topics of crime and violence. What fascination might the theological and political disputes of the 14th century hold for the 20th-century reader – the rivalries between Pope and emperor, bishops and abbots, between reformist friars who preach poverty and wealthy clerics who support the church's claims to property? Is all this palatable only because it is part of an ingenious detective story in which a Sherlock Holmesian English friar, aptly named Brother William of Baskerville, assisted by a naive young monk called Adso, solves the puzzle of a series of lurid and mysterious deaths?

How might we explain the best-selling success of The Name of the Rose, a novel by an Italian academic set in a medieval abbey where the focus of monastic life (along with prayer) is the preservation of a vast library?

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)